In my mind, Friday = cocktails. If I quit drinking, would it mean better health and ripped abs? Or is that end-of-week Old Fashioned actually good for me? ++++ “Should I take a break from booze?” Have you ever asked yourself this question? I have. I never felt like I needed to quit drinking. My consumption is normal by most accounts. It’s “moderate.” But boozy beverages seem to show up a lot. I like having a beer to mark the end of a work day. I like a good glass of wine or two with Sunday dinner. Friday night just…

In my mind, Friday = cocktails. If I quit drinking, would it mean better health and ripped abs? Or is that end-of-week Old Fashioned actually good for me?

++++

“Should I take a break from booze?”

Have you ever asked yourself this question?

I have.

I never felt like I needed to quit drinking. My consumption is normal by most accounts. It’s “moderate.”

But boozy beverages seem to show up a lot.

I like having a beer to mark the end of a work day. I like a good glass of wine or two with Sunday dinner. Friday night just seems to call for a cocktail.

Something to celebrate? Pour a little champagne. Crappy day? A martini will take the edge off.

The drinks can start to add up.

They’re easy to justify: I’m a healthy person. I work out a lot. I eat good food.

But could giving up alcohol be a tipping point? Am I missing sharper thinking and perfect sleep and hypercharged creativity and young skin and a six pack because of my six packs?

Is alcohol slowly, silently chipping away at my health?

After all, I’ve read that drinking can wreak havoc on the body and mind…

Or, wait, was it that drinking is good for your heart?

Or bad for your heart but you still live longer?

How do my wellness goals square with the delicious craft beer in my fridge?

I want to be healthy. Like most people I want to look and feel my best.

Curious about how alcohol affects that goal, I started digging. When it comes to alcohol’s effect on health, the picture is kind of confusing.

You may have heard that drinking is actually good for you.

Moderate alcohol intake is associated with a lower risk of diabetes, gallstones, and coronary heart disease.

Light to moderate drinking seems to be good for the heart and circulatory system, helping reduce your risk of cardiac arrest and clot-caused stroke by 25 to 40 percent.

And there have been several studies indicating that drinkers — even heavy drinkers — actually outlive people who don’t drink.

We see headlines about all this every time a new study comes out, which seems fairly often, judging by my newsfeed.

An important point that seems to get buried: If you don’t already drink, health experts recommend you don’t start.

Wait, what? If drinking is so good for you, then why not add that antioxidant-rich red wine to MyPlate — a nice goblet right where the milk used to be?

No one knows if any amount of alcohol is really good for all of us.

Don’t worry, I’m not going to tell you not to drink. (Spoiler alert: I did not take a break from booze.)

Most of the research on alcohol’s potential health benefits are large, long-term epidemiological studies. This type of research never proves anything. Rather than show cause, it shows correlation.

What’s the difference between correlation and causation?

Well, imagine that every time you saw someone open an umbrella, it was raining. Because of this correlation, you concluded that umbrella opening causes it to rain. That would be mistaking cause with correlation.

So even though many studies suggest that light to moderate drinkers have lower rates of the above-mentioned health problems than non-drinkers, that doesn’t mean drinking causes those benefits.

Sure, it could be that alcohol consumption raises HDL (“good”) cholesterol. Or it could be that moderate drinking reduces stress.

Or it could be that drinking doesn’t cause any health benefit.

Rather, it could be that people who drink a light to moderate amount also have something else going on in their lives, unrelated to alcohol consumption, that keeps them healthier.

According to Dr. Spencer Nadolsky, a board-certified family physician in Maryland and Precision Nutrition coach and contributor: “It might be something inherent, like genetics or a personality trait that has them enjoying a low-stress life.”

“Maybe it’s a different lifestyle factor. We just don’t know.”

Plus, any physiological effects would vary by individual. The amount of alcohol that may help your heart health might be really detrimental to your friend’s — for instance, if he has a history of high blood pressure.

And most of the research indicates that you’d have to be a light to moderate drinker with no heavy drinking episodes (even isolated ones) to see a heart benefit.

Lots of drinkers don’t know how much alcohol they actually consume, anyway.

Moderation: We hear that word so often in conversations about health and diet that it starts to seem meaningless.

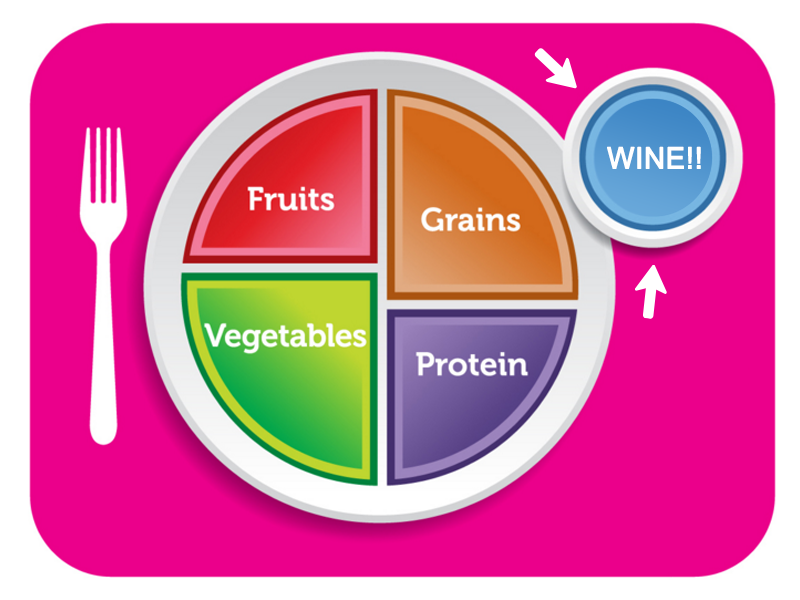

Definitions vary around the world, but according to the United States Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, “moderate drinking” means, on average:

- For women: up to seven drinks per week, with no more than three drinks on any single day

- For men: up to 14 drinks per week, with no more than four drinks on any single day

And here’s a guide to health-agency classified “drinks”:

Sure, you might know you’re not a binge drinker (that’s five or more drinks for men, or upwards of four for women, within two hours).

But when was the last time you poured wine in a measuring cup, or tallied your drinks total at the end of the week, or calculated your weekly average in a given month, or adjusted your tally to account for that sky-high 9.9% ABV lager you love?

Studies show that people routinely, sometimes drastically, underestimate their alcohol consumption.

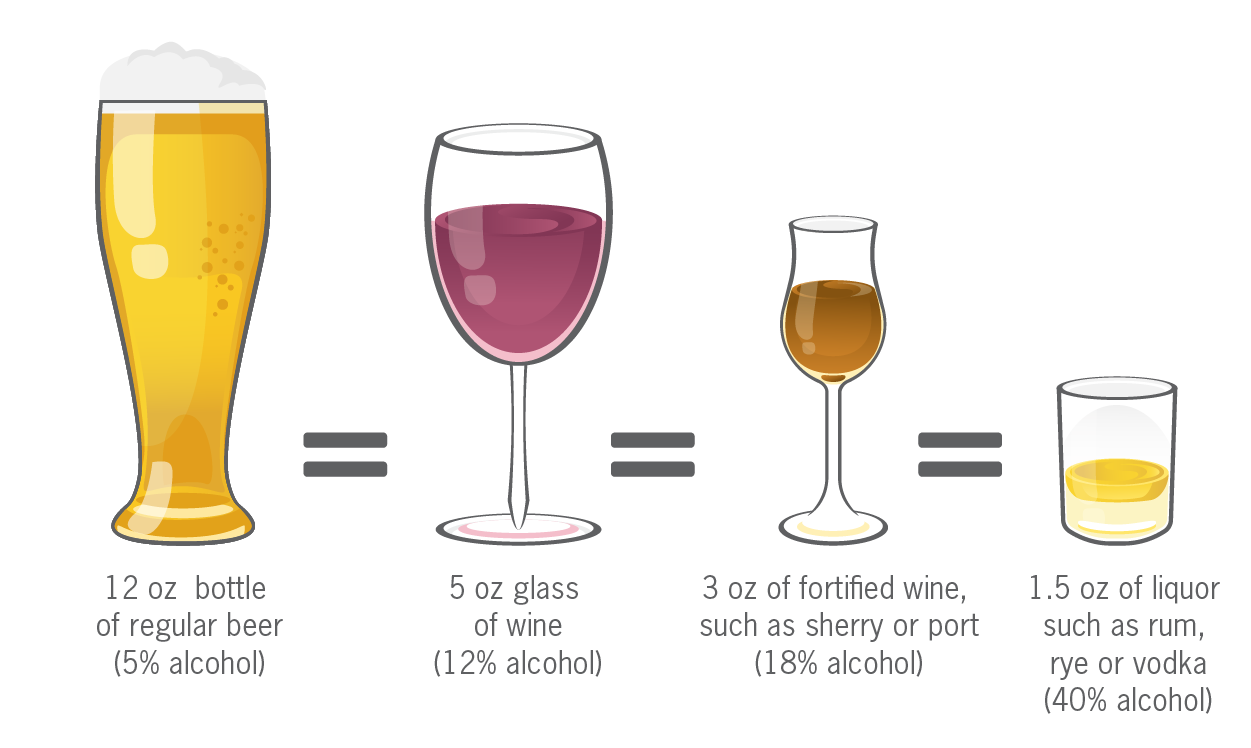

It’s easy to edge into the “heavy” category without realizing it. For example, if you’re a woman:

That’s a big problem, since heavy drinking comes with a much higher risk of major health problems.

Risks associated with moderate and heavy alcohol consumption

| Moderate | Heavy | |

|---|---|---|

| Heart | Arrhythmias High blood pressure Kidney disease Heart disease Stroke |

|

| Brain | Disinhibition Altered judgement Poor coordination Sleep disruption Alcoholism* |

Chemical dependence Depression Alcoholism Neurological damage Epilepsy Dementia Damage to developing brains |

| Immunity | Infection / illness / lowered immune response Cancer (mouth, throat, esophagus, liver, breast) Damaged intestinal barrier Increased inflammation / flare-ups of autoimmune disorders |

|

| Hormones | Breast cancer | Hormone disruption Impaired sexual function Impaired reproductive function Thyroid disease |

| Liver | Worsening of existing conditions such as hepatitis | Fatty liver Alcoholic hepatitis Fibrosis / cirrhosis Hepatocellular Liver cancer |

| Metabolism | Weight gain or stalled weight loss** Interference with some medications |

Loss of bone density Bone fractures Osteoporosis Anemia Pancreatitis Changes to fat metabolism Muscle damage |

*Particularly if there’s alcoholism in your family **If drinking causes you to eat more food or opt for energy-dense meals

In young males especially, even moderate drinking increases the risk of accidental injury or death, due to the “Hey y’all, hold my beer and watch this!” effect, or simply the dangerous equation of youthful exuberance combined with less impulse control, combined with more peer pressure, combined with things like motor vehicles and machinery.

All drinking comes with potential health effects.

After all, alcohol is technically a kind of poison that our bodies must convert to less-harmful substances for us enjoy a good buzz relatively safely.

Through a series of chemical pathways using the enzymes alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), we convert ethanol to acetaldehyde, then to acetate. The body breaks acetate down into carbon dioxide and water.

A second system for processing alcohol, the microsomal ethanol oxidizing system (MEOS), involves cytochrome P450 (CYP), an enzyme group that chemically affects potentially toxic molecules (such as medications) so they can be safely excreted.

In light to moderate drinkers, only about 10 percent of ethanol processing is done by the MEOS. But in heavy drinkers, this system kicks in more strongly. That means the MEOS may be less available to process other toxins. Oxidative cell damage, and harm from high alcohol intake, then goes up.

The biochemistry doesn’t matter as much as the core concepts:

1. We have to change alcohol to tolerate it.

2. Our ability to process alcohol depends on many factors, such as:

- our natural individual genetic tolerance;

- our ethnicity and genetic background;

- our age;

- our body size;

- our biological sex;

- our individual combinations of conversion enzymes;

- etc.

3. Dose matters. But all alcohol requires some processing by the body.

So then the question becomes: What’s the “sweet spot”?

What amount of alcohol balances enjoyment (and your jokes becoming funnier) with your body’s ability to respond and recover from processing something slightly poisonous?

The moderate-vs-heavy guidelines are the experts’ best guess at the amount of alcohol that can be consumed with statistically minimal risk, while still accounting for what a lot of people are probably going to do anyway: drink.

It doesn’t mean that moderate drinking is risk-free.

But drinking is fun. (There, I said it.)

In North America, we tend to separate physical well-being from our emotional state. In reality, quality of life, enjoyment, and social connections are important parts of health.

I enjoy drinking.

So do a lot of other people.

In the U.S., for example, 65 percent of people say they consume alcohol. Of those drinkers, at least three quarters enjoy alcohol one or more times per week.

The wine flows at lunchtime in continental Europe (for Scandinavians, it’s the light beer lättöl). Hitting a pub or two after work is standard procedure in the UK and Japan. Northern Europeans swear by their brennivin, glögg, or akvavit (not to mention vodka). South America and South Africa alike are renowned for their red wines.

Thus, for much of the world’s population, alcohol — whether beer, wine or spirits — is something of a life staple.

And if you’re doing it right — meaning tasteful New Year’s Eve champagne toasts are more common in your life than shot-fueled bar dances to “Hotline Bling” — there are some undeniable benefits to be gained:

- Pleasure: Assuming you’ve graduated from wine coolers and cheap tequila shots, alcoholic beverages usually taste pretty darn delicious.

- Leisure: A bit of alcohol in your bloodstream does help you feel relaxed. And like a good meal, a good glass of wine should offer the opportunity to slow down for a minute.

- Creativity: There’s evidence that when you’re tipsy, you may be more successful at problem-solving thanks to increased out-of-the-box thinking.

- Social connection: Drinking may contribute to social bonding through what researchers call “golden moments” — when you all smile and laugh together over the same joke. This sense of community, belonging, and joy can contribute to your health and longevity.

So drink because you genuinely enjoy it.

Drink if it truly adds value and pleasure to your life.

Not because:

- you’re stressed; or

- it’s a habit; or

- other people around you don’t want to drink alone; or

- it’s “good for you”.

With confusing alcohol consumption categories and contradictory news headlines, many people give up trying to decide whether drinking is healthy or not.

A new study shows alcohol may be harmful? Whatever.

Or:

Drinkers live longer? I’ll hop on that horse and ride it straight to the bar!

Forget about the potential health benefits of alcohol.

There are plenty of (probably better) ways to reduce your risk of cardiovascular disease — like eating well, exercising, and not smoking.

Wanting the enjoyment of a perfect Old Fashioned or a rare sake is a legitimate — probably the best — reason to drink.

As with what you eat, what you drink should be purposeful and mindful. And delicious.

Drinking or not drinking isn’t about ‘healthy vs. not’. It’s about tradeoffs.

Alcohol is just one factor among many that affect physical performance, health, and fitness. Whether to keep drinking or cut back depends on how much you drink, what your goals are, and how you want to prioritize those things.

How to sort it all out? I touched base with Krista Scott-Dixon, Ph.D., curriculum designer for Precision Nutrition’s Coaching programs for men and women.

She said to think of it this way: In order to say “yes” to something, you have to say “no” to something else. And only you know what you are, or aren’t, willing to trade.

- Saying “yes” to six-pack abs might mean saying “no” to two drinks at the bar.

- Saying “yes” to Friday happy hour might mean saying “no” to your Saturday morning workout.

- Saying “yes” to marathon training might mean saying “no” to boozy Sunday brunches.

- Saying “yes” to better sleep (and focus, and mood) might mean saying “no” to your daily wine with dinner.

- Saying “yes” to avoiding the nacho platter might mean saying “no” to the second margarita.

- Saying “yes” to moderate alcohol consumption might mean finding a way to say “no” to stress triggers (or human triggers) that make you want to drink more.

The decisions you make will also depend on what you’re willing to do — and not willing to do.

- Maybe you’re willing to have one less beer a day, but you’re not willing to kiss it goodbye altogether.

- Maybe you’re willing to practice drinking more slowly and mindfully, but you’re not willing to decrease your total alcohol intake.

- Or, maybe you’re willing to stay sober during most social situations, but you’re not willing to endure your partner’s office party without a G&T on hand.

- Maybe you’re willing to upgrade to a fancier bottle, but you’ll bite someone’s face off if they try to take away your Australian shiraz.

Maybe there is a “best” answer for how much alcohol is okay for everyone. But we don’t know what it is yet.

At least not for certain.

As I researched this article, I became more aware of my own drinking habits. And I started to wonder whether I should improve them.

I’ve started to drink more mindfully, asking myself questions here and there about why and what I’m drinking. As I did this, I noticed myself drinking less.

A couple weeks ago when I was out with some friends, while they threw back multiple pints, I slowly sipped a single serving of the bar’s finest Scotch. It felt (and tasted) good. We’ll see if it’s a tipping point for further improvement — and even better health.

What to do next:

Some tips from Precision Nutrition

Following the guidelines for moderate drinking is a good start.

But here’s what the guidelines don’t tell us: Alcohol’s effects (both its potential risks and benefits) vary widely from person to person, depending on genetics, size, sex, age, history with alcohol, and overall health.

Let your body take the lead. Read its cues. Observe yourself carefully, gather data, and see how alcohol is — or is not — working for you.

1. Observe your drinking habits.

Keep track of all the alcohol you drink for a week or two (here’s a worksheet to help you). You don’t need to share it with anyone or assume any change is necessary. Just collect the info.

Next, review the data. Ask:

- Am I drinking more than I thought? Maybe you hadn’t been taking the couple causal beers with Sunday NFL into account.

- Is my drinking urgent, mindless, or rushed? Slamming drinks back without stopping to savor them can be a sign that drinking is habitual, not purposeful.

- Are there themes or patterns in my drinking? Perhaps you habitually over-drink on Friday because your job is really stressful.

- Is alcohol helping me enjoy life, or is it stressing me out? If you’re not sleeping well or feeling worried about the drinking, the cost can outweigh the benefit.

- Does alcohol bring any unwanted friends to the party? Binge eating, drug use, texting your ex?

If any of the answers to these questions raise red flags for you, consider cutting back and seeing how you feel.

2. Notice how alcohol affects your body.

Use Precision Nutrition’s “how’s that working for you?” litmus test. Ask:

- Do I generally feel good? Simple, but telling.

- When I drink, do I experience a hangover, digestive distress, sleep problems, anxiety, or other discomfort? These can be signs that you’re drinking too much or that your body can’t handle what you’re throwing at it.

- Is my blood pressure still in the healthy range?

- How’s my physical performance after drinking? If you work out the next morning, how does that go? Are you recovering well?

If you’re unsure about whether your alcohol use is helping or hurting you, talk to your doctor and get a read on your overall health.

3. Notice how alcohol affects your thoughts, emotions, assumptions, and general perspective on life.

Again: How’s that working for you?

- Do you feel in control of your drinking? Are you choosing, deliberately and purposefully… or “finding yourself” drinking?

- What kind of person are you when you are drinking? Are you a bon vivant, just slightly wittier and more relaxed, savoring a craft beer with friends? Or are you thinking, Let’s make that crap circus of a workday go away, as you pound back the liquid emotional anesthetic through gritted teeth?

- If you had to stop drinking for a week, what would that be like? No big deal? Or did you feel mild panic when you read that question?

4. Play ‘Let’s Make a Deal’.

To pinpoint which goals and activities in your life are the most important to you, ask yourself:

- What am I currently saying “yes” to?

- What am I currently saying “no” to?

- What am I willing to say “yes” to?

- What am I willing to say “no” to?

- What am I prepared to say “yes” and “no” to? Why?

There are no right or wrong answers. Just choices and compromises.

You’re a grownup who can think long-term and weigh options rationally. Whether you drink or not is your call.

5. Disrupt the autopilot.

One of the keys to behavior change is moving from unconscious, automatic reactions to conscious, deliberate decisions.

To experiment with decreasing your alcohol intake, try these strategies:

- Delay your next drink. Just for 10 minutes, to see if you still want it.

- Look for ways to circumvent your patterns. If you usually hit the bar after work, try booking an alcohol-free activity (like a movie date or a yoga class) with a friend instead. If you stock up on beer at the grocery store, skip that aisle altogether and pick up some quality teas or sparkling water instead.

- Savor your drink. Tune into the sensations in front of you. Here’s an idea: try tasting wine like a sommelier. Look at it, swirl it, sniff it, taste it.

- Swap quantity for quality. Drink less, but when you do drink, treat yourself to the good stuff.

6. Call on the experts.

Change almost always works better with support. It’s hard to change alone.

- Talk to your doctor about your drinking patterns and your health.

- Consider genetic testing. If you are at risk for breast cancer, avoiding alcohol might be a good idea. On the other hand, if you’re at risk for cardiovascular disease, 1-2 drinks a night may be a good thing.

- Get nutrition coaching. Precision Nutrition coaches specialize in helping clients optimize diet and lifestyle patterns for good.

7. If you choose to drink, enjoy it.

Savor it. Enjoy it mindfully, ideally among good company.

Eat, move, and live… better.

The health and fitness world can sometimes be a confusing place. But it doesn’t have to be.

Let us help you make sense of it all with this free special report.

In it you’ll learn the best eating, exercise, and lifestyle strategies — unique and personal — for you.

Click here to download the special report, for free.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

Alcohol: Balancing the Risks and the Benefits. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Alcohol and Heart Disease. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Alcohol and Public Health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (Website.)

Alcohol research group (website) 2015.

Allen, Naomi E., et al. Moderate alcohol intake and cancer incidence in women. J Natl Cancer Inst (2009) 101 (5): 296-305. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn514

Andrews, Ryan. (Email exchange.) October 15, 2015.

Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Hedden SL, Kennet J, Lipar r, Medley G, Tice P. 2015.

Brooks PJ, Zakhari S. Moderate alcohol consumption and breast cancer in women: from epidemiology to mechanisms and interventions.

Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013 Jan;37(1):23-30. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01888.x.

Cao Y, Willett WC, Rimm EB. Light to moderate intake of alcohol, drinking patterns, and risk of cancer: results from two prospective US cohort studies. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 2015, Aug.;351():1756-1833.

Ceni E, Mello T, Galli A. Pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease: role of oxidative metabolism. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Dec 21;20(47):17756-72. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i47.17756.

Chartier KG, Vaeth PAC, Caetano R. Focus On: Ethnicity and the Social and Health Harms From Drinking. Alcohol Research : Current Reviews. 2014;35(2):229-237.

Cherpitel CJ. Focus on: The Burden of Alcohol Use—Trauma and Emergency Outcomes. Alcohol Research : Current Reviews. 2014;35(2):150-154.

Coronado GD, Beasley J, Livaudais J. Alcohol consumption and the risk of breast cancer. Salud Publica Mex. 2011 Sep-Oct;53(5):440-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22218798

Druesne-Pecollo N, et al. Alcohol drinking and second primary cancer risk in patients with upper aerodigestive tract cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014 Feb;23(2):324-31. doi: 0.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0779.

Dumitrescu RG, Shields PG. The etiology of alcohol-induced breast cancer. Alcohol. 2005 Apr;35(3):213-25. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16054983

European action plan to reduce the harmful use of alcohol 2012-2020. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. 2012.

Ferrières J. The French paradox: lessons for other countries. Heart. 2004 Jan; 90(1): 107–111.

Ganesan M, et al. Acetaldehyde accelerates HCV-induced impairment of innate immunity by suppressing methylation reactions in liver cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015 Oct 1;309(7):G566-77. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00183.2015. Epub 2015 Aug 6.

Garbutt, JC. Phone interview. January 25, 2016.

Jarosz AF, Colflesh GJH, Wiley J. (2012). Uncorking the muse: Alcohol intoxication facilitates creative problem solving. Consciousness and Cognition, 21, 487–493.

Johnston, Ann Dowsett. Drink. The Intimate Relationship Between Women and Alcohol. 2013. Harper Collins.

Knott CS, Coombs N, Stamatakis E, Biddulph JP. All cause mortality and the case for age specific alcohol consumption guidelines: pooled analyses of up to 10 population based cohorts. BMJ. 2015; 350 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h384

Larsson SC, Drca N, Wolk A. Alcohol consumption and risk of atrial fibrillation: a prospective study and dose-response meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014; Sep.;64(3):1558-3597.

Laurberg P, Andersen S, Pedersen IB, Knudsen N, Carlé A. Prevention of autoimmune hypothyroidism by modifying iodine intake and the use of tobacco and alcohol is manoeuvring between Scylla and Charybdis. Hormones (Athens). 2013 Jan-Mar;12(1):30-8.

Luo J. Autophagy and ethanol neurotoxicity. Autophagy. 2014;10(12):2099-108. doi: 10.4161/15548627.2014.981916.

Liu Y, Nguyen N, Colditz GA. Links between alcohol consumption and breast cancer: a look at the evidence. Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2015 Jan;11(1):65-77. doi: 10.2217/whe.14.62.

Miller, William R, Munoz, Ricardo F. Controlling Your Drinking. Tools to Make Moderation Work For You. 2nd Edition. 2013. The Guildford Press.

Molina PE, Gardner JD, Souza-Smith FM, Whitaker AM. Alcohol Abuse: Critical Pathophysiological Processes and Contribution to Disease Burden. Physiology. 2014;29(3):203-215. doi:10.1152/physiol.00055.2013.

Nadolsky, Spencer. (Phone Interview.) November 23, 2015.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Website. http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/

Northcote J, Livingston M. Accuracy of Self-Reported Drinking: Observational Verification of ‘Last Occasion’ Drink Estimates of Young Adults. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46(6):709-713.

O’Keefe JH, Bhatti SK, Bajwa A, DiNicolantonio JJ, Lavie CJ. Alcohol and cardiovascular health: the dose makes the poison…or the remedy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014 Mar;89(3):382-93. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.11.005.

Osna NA, et al. Hepatitis C, innate immunity and alcohol: friends or foes? Biomolecules. 2015 Feb 5;5(1):76-94. doi: 10.3390/biom5010076.

Parry CD, Patra J, Rehm J. Alcohol consumption and non-communicable diseases: epidemiology and policy implications. Addiction. 2011 Oct;106(10):1718-24. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03605.x.

Peele S, Grand M (Eds.). Alcohol and pleasure: A health perspective. Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel, pp. 187-207. 1999 Stanton Peele.

Poli A, et al. Moderate alcohol use and health: a consensus document. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013 Jun;23(6):487-504. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2013.02.007. Epub 2013 May 1.

Q&A – How can I drink alcohol safely? Lars Møller, Programme Manager, Alcohol and Illicit Drugs at WHO/Europe. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe.

Rehm J, Baliunas D, Borges GL, et al. The relation between different dimensions of alcohol consumption and burden of disease: An overview. Addiction. 2010a;105(5):817–843.

Rehm J, Gmel G, Sepos CT, Trevisan M. Alcohol-related morbidity and mortality. Alcohol Research and Health 2003;27(1)39–51.

Ridley N J, Draper B, Withall A. Alcohol-related dementia: an update of the evidence. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2013; 5(1): 3.

Roerecke M, Rehm J. Alcohol intake revisited: risks and benefits. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2012 Dec;14(6):556-62. doi: 10.1007/s11883-012-0277-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22864603

Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion: 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2015.

Scoccianti C, Straif K, Romieu I. Recent evidence on alcohol and cancer epidemiology.

Future Oncol. 2013 Sep;9(9):1315-22. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.94.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24512927

Scott-Dixon, Krista. (Phone Interview.) October 14, 2015.

Shatzker, Mark. How flavor drives nutrition. Wall Street Journal, April 9, 2015.

Shield KD, Parry C, Rehm J. Chronic diseases and conditions related to alcohol use. Alcohol Res. 2013;35(2):155-73.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3908707/

Suter PM, Tremblay A. Is Alcohol Consumption a Risk Factor for Weight Gain and Obesity? Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences, 2005; 42:3, 197-227 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10408360590913542

Szabo G, Saha B, Bukong TN. Alcohol and HCV: implications for liver cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;815:197-216. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-09614-8_12.

Umberson D, Montez JK. Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav. 2010; 51(Suppl): S54–S66.

Valeix, Pierre, et al. Effects of light to moderate alcohol consumption on thyroid volume and thyroid function. Clinical Endocrinology 68, no. 6 (June 2008): 988–995.

Varela-Rey M, Woodhoo A, Martinez-Chantar ML, Mato JM, Lu SC. Alcohol, DNA methylation, and cancer. Alcohol Res. 2013;35(1):25-35.

Wang L, Lee I-M, Manson JE, Buring JE, Sesso HD. Alcohol Consumption, Weight Gain, and Risk of Becoming Overweight in Middle-aged and Older Women. Archives of internal medicine. 2010;170(5):453-461. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.527.

Yang F, Luo J. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and ethanol neurotoxicity. Biomolecules. 2015 Oct 14;5(4):2538-53. doi: 10.3390/biom5042538.

Yeomans MR. Alcohol, appetite and energy balance: is alcohol intake a risk factor for obesity? Physiol Behav. 2010;100:82–9. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.01.012.

Zakhari S, Hoek JB. Alcohol and breast cancer: reconciling epidemiological and molecular data. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;815:7-39. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-09614-8_2.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25427899

Zhang C, et al. Alcohol intake and risk of stroke: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Cardiol. 2014 Jul 1;174(3):669-77. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.225.

Source: Would I be healthier if I quit drinking? My quest to understand the real tradeoffs of alcohol consumption. : Precision Nutrition