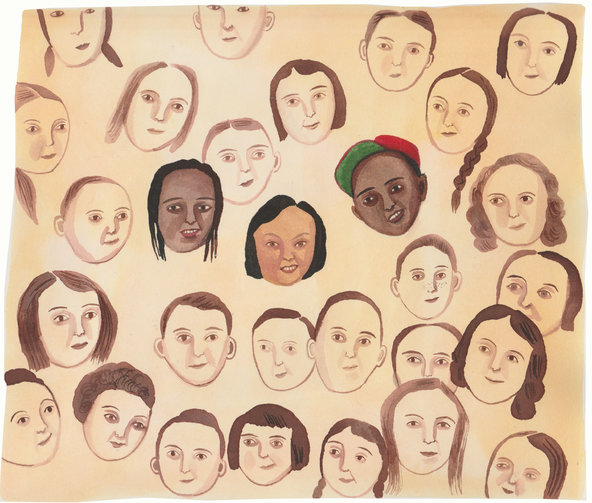

Credit Giselle Potter

Clicking through the new website of the private school my three children attend, I landed on a close-up photo of my oldest child’s smiling face. I shouldn’t have felt jarred, but I did. The picture, accompanied by a short interview highlighting everything she loves about the school, had been posted on the admissions page. Born in India and adopted by my husband and me, who are white, she’s a minority student at a majority white school that’s striving to become more diverse. Her interview was one of many, but for me, her mother, it generated a spotlight’s heat.

My older daughter is 14. Our son and younger daughter, siblings born in Ethiopia, are 13 and 12. When the children were small, strangers often mistook them for adorable, boisterous triplets. The kids’ friendly smiles and our family’s multicultural makeup ensured that we attracted attention everywhere we went. More than once, professional photographers stopped us on the street to propose a photo shoot. Religious strangers felt compelled to thank my husband and me for “loving the Lord and loving orphans.” Shoppers in the grocery store flagged me down to gush, “Your family is beautiful.”

The idea of us made a lot of people feel good, hopeful even, but I quickly grasped that we could also be perceived by some as a kind of entertaining novelty. For years, another mom at our elementary school referred to me, in public and private, as “Angelina Jolie.” I did my best to shield the kids, and myself, from the attention, so that our family could be just that — a family, not a symbol of post-racial equality or evidence of a supposed Hollywood trend, a trend some critics characterized as white celebrities adopting black babies as fashion accessories.

By virtue of their white parents, transracial adoptees often move in majority white spaces, inadvertently providing diversity for others. Although I’ve always tried to place my kids in environments where they encounter peers and role models of the same race, they inevitably end up in the minority at school, at camps, in enrichment classes and on sports teams.

Early on I noticed how schools and kids’ programs love to feature children of color in their marketing materials to highlight their commitment to diversity, just as the big corporations do. As much as I wanted pictures of my three to entice more minority children to join my children in their activities, I couldn’t bring myself to sign the blanket photo releases that came with every registration packet. I didn’t want my children being used to promote an ideal of diversity that didn’t exist in reality.

But complications arose. Without my release, my son’s fourth-grade teacher couldn’t post group pictures to her classroom website, an inconvenience that didn’t seem fair to her. Then a photo of my daughter, taken without my knowledge at our town’s Christmas parade, popped up in a catalog for the recreation department. A picture of all three kids appeared in a brochure for their favorite summer camp, even though I’d specified no photos. Complaining after the fact felt petty and pointless when I couldn’t identify any tangible harm done.

And then there was the problem of my work as a writer. Frequently when I published a parenting essay, the editor would want to run a family photo. For years I resisted, putting myself at a distinct disadvantage in the world of mommy blogs and image-centric parenting websites. As the kids matured, I discussed the pros and cons of every photo request with the whole family. The kids voted to publish the photo every time, and sometimes I did. Although I’ve been careful to never include their real names in my work to guard their privacy, there’s no question that using my children’s photos on occasion has helped my professional career, a reality I’m conflicted about, even if my kids are not.

And so I gave up. These days I sign all the photo releases for schools and camps and teams because this is the way the world works. All I can do as a parent is maintain an ongoing dialogue with my children about the hidden messages in advertising, about the ways minorities are portrayed in the media, and about why I feel so protective of their likenesses.

Sometimes, when I find a picture of my daughter playing bass guitar on the girls’ rock camp Facebook page or discover a video of my son’s deft footwork being tweeted by his soccer club, I’m thrilled. To see my kids promoted for what they do, not what they look like, feels good. Finding them featured in a camp catalog or a school brochure doing nothing but looking “ethnic” alongside their white peers brings up less positive emotions.

The photo and interview on the school admissions page felt like a “do nothing” at first, even though the school does a good job representing students of all backgrounds in its marketing as a whole. The post also felt like an intrusion. I’d never signed a release for an interview, and nobody had warned me it was coming, let alone sought my permission.

“Did you know they were going to put this interview with you on the website?” I asked my daughter.

“Of course,” she said.

“And you’re O.K. with it?”

“Obviously.”

She’d made her decision. With my children approaching adulthood in the age of the selfie, they’ll be making decisions daily about how to use and distribute their own images, with their status as members of minority groups an added twist. As a mom who shies away from the camera, I hope I’ve given them the tools to figure it out.

Sharon Van Epps is a freelance writer.

Related:

- Donating an Organ to My Son

- Fighting Heroin Addiction With My Mother on My Side

- We Lost Our Soldier, but We’re Still a Family

- View all of Ties.

Sign up for the Well Family newsletter to get the latest news on parenting, child health and relationships with advice from our experts to help every family live well.