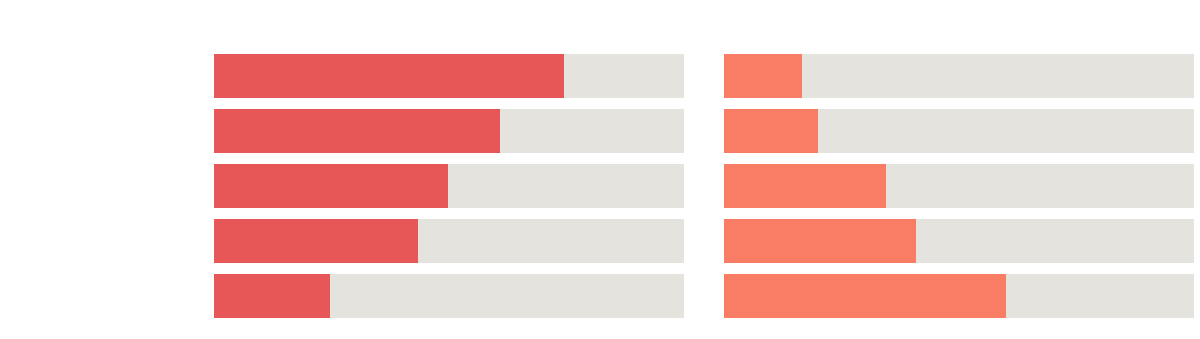

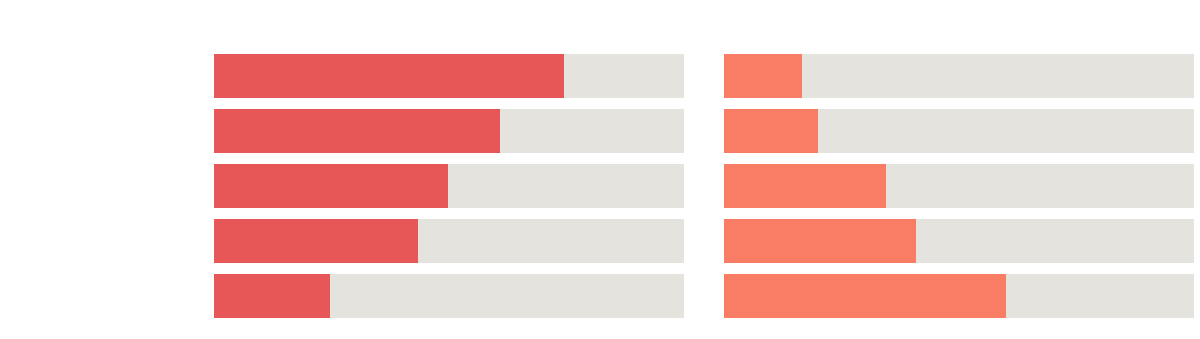

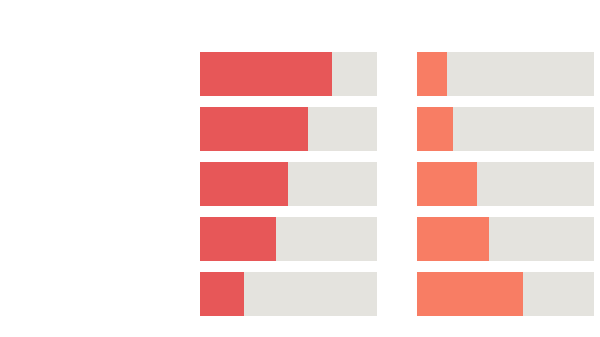

Hosts granted preapproval to 75 percent of travelers who made no mention of a disability, according to the study. That rate fell to 61 percent for those who said they had dwarfism, 50 percent for those with blindness, 43 percent for those with cerebral palsy and just 25 percent for those with spinal cord injuries.

Some of that disparity can be explained by hosts who followed up with questions for the travelers with disabilities, the researchers said, thus preventing the request from being classified as preapproved. Requests were sent to hosts throughout the country over a nearly six-month period last year.

The researchers could not solely blame the findings on personal prejudice. They said physical inaccessibility was a major factor behind the disparity in hosts’ responses. That, they said, raised concerns that businesses like Airbnb could exclude users with disabilities even as they expand access to services over all.

“Here’s the flip side of our tech revolution: Platforms like Airbnb seem to be perpetuating or increasing opportunities for exclusion, both economic and social,” said Lisa Schur, a professor in the Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations and one of the study authors.

With more than three million listings, Airbnb has introduced new lodging options around the world, including many that meet the needs of people with disabilities. Last year, the company also instituted a nondiscrimination policy and took steps to better handle complaints of bias, including assurances that users treated unfairly will have a place to stay.

“Discrimination of any kind on the Airbnb platform, including on the basis of ability, is abhorrent, a violation of our anti-discrimination policy and will result in permanent removal from our platform,” the company said in a statement. The majority of Airbnb reservations, it noted, are made by “instant booking,” which does not require preapproval.

The Disability Gap on Airbnb

Travelers with disabilities are more likely to have lodging requests rejected and less likely to have them pre-approved than those without, according to a Rutgers University study.

Preapprovals

Rejections

No disability

Cerebral palsy

Spinal cord injury

Preapprovals

Rejections

No disability

Cerebral palsy

Spinal cord injury

Still, like many businesses in the sharing economy, Airbnb operates in a regulatory haze, and protections imposed on other forms of lodging under the Americans with Disabilities Act may not always apply to Airbnb listings, which are often a homeowner’s primary or secondary residence.

“If we’re entering an era where these new types of hotels, which are essentially private homes, can’t offer accommodations, it defeats and undoes all of the progress we’ve made with the A.D.A. as far as equal access is concerned,” said Mason Ameri, one of the authors of the Rutgers study and a postdoctoral fellow at the university’s School of Management and Labor Relations. “The law needs to catch up with services like Airbnb.”

Alice Wong, a former member of the National Council on Disability and founder of the Disability Visibility Project, said that if Airbnb did not lay out and enforce strict guidelines for listings that claim to be handicapped accessible, the company was making a false promise to travelers.

“Discrimination is often based on ignorance,” said Ms. Wong, who is in a wheelchair. “People with disabilities deviate from the image of a typical customer, so the way they are discriminated against is hard to pin down but very real.”

Some hosts in the study, like the ones who denied Ms. Garcia, rejected inquiries from Mr. Ameri and his colleagues with little explanation. Others referred the fictitious traveler to listings that could better accommodate their needs or asked what could be done to make the listed space more accessible. A few made rude or insensitive remarks.

The introduction of Airbnb’s nondiscrimination policy in September had little effect on the findings of the study, which was conducted from June to mid-November, the authors said. In fact, some hosts violated those guidelines, which ban rejecting or charging extra for assistance animals. But, the authors acknowledge, that may change as hosts become more familiar with the rules.

Airbnb is valued at about $30 billion. The market capitalization of Hilton Hotels is nearly $22 billion.

To improve access to homes by the disabled, the researchers suggest that Airbnb make sure hosts understand and follow federal disability guidelines, and engage with advocacy organizations and travelers with disabilities to understand their needs and frustrations.

Technology has long created opportunities for people with disabilities, Ms. Wong said, whose life has been “tremendously positively impacted by tech,” she said.

“But tech is really slow to catch up with regard to human rights issues,” she added. “The new platforms amplify the way people already do things. That’s how people get left out of opportunities, especially people who are already marginalized.”

Airbnb said that it has teamed with several disability organizations to better educate hosts and that it expects to release new accessibility listing and filtering features this summer.

“This is just the start, and we will continue to engage experts and leaders in this area to ensure our community is open and accessible to everyone,” the company said in the statement.

Other options have sprouted up, too. Accomable, a listing platform designed by and for travelers with disabilities, has 1,100 listings in 60 countries.

In the meantime, disability advocates say that travelers with disabilities should do exactly what Ms. Garcia did: Ask lots of questions.